This is the first articles in a series to explain the basics of Ubuntu Development in a way that does not require huge amounts of background and goes through concepts, tools, processes and infrastructure step by step. If you like the article or have questions or found bugs, please leave a comment.

Introduction to Ubuntu Development

Ubuntu is made up of thousands of different components, written in many different programming languages. Every component – be it a software library, a tool or a graphical application – is available as a source package. Source packages in most cases consist of two parts: the actual source code and metadata. Metadata includes the dependencies of the package, copyright and licensing information, and instructions on how to build the package. Once this source package is compiled, the build process provides binary packages, which are the .deb files users can install.

Every time a new version of an application is released, or when someone makes a change to the source code that goes into Ubuntu, the source package must be uploaded to Launchpad’s build machines to be compiled. The resulting binary packages then are distributed to the archive and its mirrors in different countries. The URLs in /etc/apt/sources.list point to an archive or mirror. Every day CD images are built for a selection of different Ubuntu flavours. Ubuntu Desktop, Ubuntu Server, Kubuntu and others specify a list of required packages that get on the CD. These CD images are then used for installation tests and provide the feedback for further release planning.

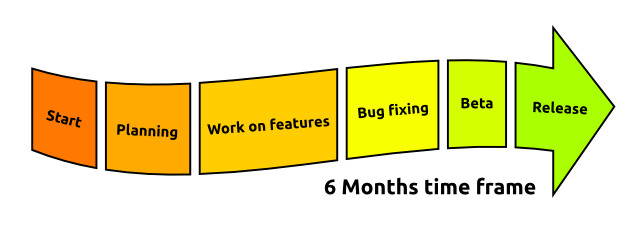

Ubuntu’s development is very much dependent on the current stage of the release cycle. We release a new version of Ubuntu every six months, which is only possible because we have established strict freeze dates. With every freeze date that is reached developers are expected to make fewer, less intrusive changes. Feature Freeze is the first big freeze date after the first half of the cycle has passed. At this stage features must be largely implemented. The rest of the cycle is supposed to be focused on fixing bugs. After that the user interface, then the documentation, the kernel, etc. are frozen, then the beta release is put out which receives a lot of testing. From the beta release onwards, only critical bugs get fixed and a release candidate release is made and if it does not contain any serious problems, it becomes the final release.

Thousands of source packages, billions of lines of code, hundreds of contributors require a lot of communication and planning to maintain high standards of quality. At the beginning of each release cycle we have the Ubuntu Developer Summit where developers and contributors come together to plan the features of the next releases. Every feature is discussed by its stakeholders and a specification is written that contains detailed information about its assumptions, implementation, the necessary changes in other places, how to test it and so on. This is all done in an open and transparent fashion, so even if you can not attend the event in person, you can participate remotely and listen to a streamcast, chat with attendants and subscribe to changes of specifications, so you are always up to date.

Not every single change can be discussed in a meeting though, particularly because Ubuntu relies on changes that are done in other projects. That is why contributors to Ubuntu constantly stay in touch. Most teams or projects use dedicated mailing lists to avoid too much unrelated noise. For more immediate coordination, developers and contributers use Internet Relay Chat (IRC). All discussions are open and public.

Another important tool regarding communication is bug reports. Whenever a defect is found in a package or piece of infrastructure, a bug report is filed in Launchpad. All information is collected in that report and its importance, status and assignee updated when necessary. This makes it an effective tool to stay on top of bugs in a package or project and organise the workload.

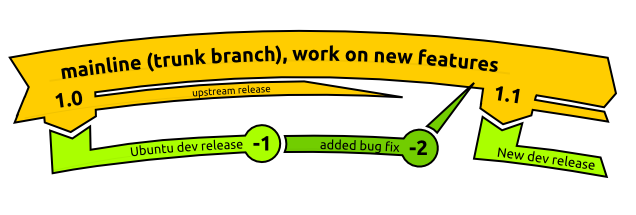

Most of the software available through Ubuntu is not written by Ubuntu developers themselves. Most of it is written by developers of other Open Source projects and then integrated into Ubuntu. These projects are called “Upstreams”, because their source code flows into Ubuntu, where we “just” integrate it. The relationship to Upstreams is critically important to Ubuntu. It is not just code that Ubuntu gets from Upstreams, but it is also that Upstreams get users, bug reports and patches from Ubuntu (and other distributions).

The most important Upstream for Ubuntu is Debian. Debian is the distribution that Ubuntu is based on and many of the design decisions regarding the packaging infrastructure are made there. Traditionally, Debian has always had dedicated maintainers for every single package or dedicated maintenance teams. In Ubuntu there are teams that have an interest in a subset of packages too, and naturally every developer has a special area of expertise, but participation (and upload rights) generally is open to everyone who demonstrates ability and willingness.

Getting a change into Ubuntu as a new contributor is not as daunting as it seems and can be a very rewarding experience. It is not only about learning something new and exciting, but also about sharing the solution and solving a problem for millions of users out there.

Open Source Development happens in a distributed world with different goals and different areas of focus. For example there might be the case that a particular Upstream might be interested in working on a new big feature while Ubuntu, because of the tight release schedule, might be interested in shipping a solid version with just an additional bug fix. That is why we make use of “Distributed Development”, where code is being worked on in various branches that are merged with each other after code reviews and sufficient discussion.

In the example mentioned above it would make sense to ship Ubuntu with the existing version of the project, add the bugfix, get it into Upstream for their next release and ship that (if suitable) in the next Ubuntu release. It would be the best possible compromise and a situation where everybody wins.

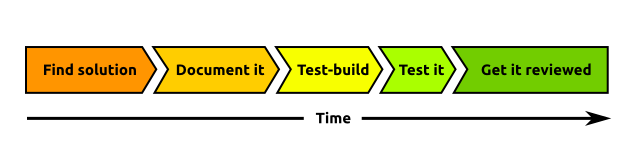

To fix a bug in Ubuntu, you would first get the source code for the package, then work on the fix, document it so it is easy to understand for other developers and users, then build the package to test it. After you have tested it, you can easily propose the change to be included in the current Ubuntu development release. A developer with upload rights will review it for you and then get it integrated into Ubuntu.

When trying to find a solution it is usually a good idea to check with Upstream and see if the problem (or a possible solution) is known already and, if not, do your best to make the solution a concerted effort.

Additional steps might involve getting the change backported to an older, still supported version of Ubuntu and forwarding it to Upstream.

The most important requirements for success in Ubuntu development are: having a knack for “making things work again,” not being afraid to read documentation and ask questions, being a team player and enjoying some detective work.

Good places to ask your questions are ubuntu-motu-mentors@lists.ubuntu.com and #ubuntu-motu on irc.freenode.net. You will easily find a lot of new friends and people with the same passion that you have: making the world a better place by making better Open Source software.

Update: Here’s Part 2 of Introduction to Ubuntu Development.